About Cass

Cass Elliot, best known as “Mama Cass” of the pop-rock group The Mamas & The Papas, was a standout talent of the 1960’s and 70’s.

A pioneer pop-culture feminist and icon, she was one of the greatest singers of her generation, and the powerhouse voice behind “California Dreamin’”, “Monday Monday”, and “Dream a Little Dream of Me” – songs which defined a new musical era by blending the genres of folk, rock and pop into a trademark sound.

Born Ellen Naomi Cohen on September 19th, 1941, Cass Elliot developed an impeccable intuition for great music. Finding her way through the 60’s folk-rock scene, Cass would go on to become one of the defining voices of the counterculture movement, and later, a beloved fixture on American television. People who knew her describe the gravity that she generated around herself, a force of self-determination, humor, and charisma that carried her throughout her career in show business. A natural-born matchmaker, Cass was at least partially responsible for the unions of Crosby, Stills & Nash, and The Lovin’ Spoonful.

Cass’s first love was the theater. However, in 1962, she traded show tunes for folk songs, where she found her place as the bold female harmony in the folk group The Big 3. Her enduring creativity followed her across her subsequent career with The Mugwumps, when at the height of Beatlemania, their record label wanted to cut her out of the group. Instead of dumping her, the group decided to disband rather than leave their cornerstone vocalist behind. By 1965, Cass had honed her chops when she banded up with her friend and former bandmate from The Mugwumps, Denny Doherty, who had by then partnered up with John and Michelle Phillips of The New Journeymen. Once Cass had joined, they renamed themselves The Mamas & The Papas.

The Mamas & The Papas were flung into the spotlight, receiving rapid commercial success following the release of “California Dreamin’”, their first single, in late 1965. The song ended up #1 on the Cash Box year end hot 100 and #10 on the Billboard year-end Hot 100 single of 1966. Other top ten hits included the Grammy® winning “Monday, Monday”, “Creeque Alley”, and “Dedicated to the One I Love”. Their first concert was held at the Hollywood Bowl, and the band went on to close the Monterey International Pop festival in 1967, alongside acts such as Jefferson Airplane, The Who, Grateful Dead and Jimi Hendrix.

Behind the group’s sun-soaked & dreamy personae, internal contentions were brewing. Cass often faced scrutiny and ridicule for her weight, and there was no denying the comparison of Mama Cass to Michelle in the public eye, either. Despite the blatant contrast, Cass stood her ground, and the crowds loved her. Unapologetically flirtatious and hilarious, Cass would charm the audience with her performances, as if she was singing just for them. In 1967, New York Magazine said about Cass, “She is a star, not despite her weight or because of it, but beyond it. Cass is a horizon.”

Likewise, Cass’s friendships in otherwise fraternal artistic circles - including Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Eric Clapton, Joni Mitchell, David Crosby, Gram Parsons, Dave Mason, and The Beach Boys - fostered her participation in pivotal moments of her time, as well as the moniker “The Queen of Los Angeles Pop Society”, coined by Rolling Stone. She garnered immense respect in a male-dominated industry, setting the stage for the then-nascent feminist movement.

Ultimately, substance abuse, betrayal, and unrequited love drove The Mamas & The Papas apart after just three short years together. The group separated in 1968 after recording four albums. Meanwhile, Cass had consciously chosen to pursue single motherhood, and her daughter Owen Vanessa was born during Cass’s final year with the band. In tandem with facing the then-social taboo of being a single parent, Cass followed with her long-awaited solo career. By the late 60’s, she was a regular on popular nighttime American television shows, even hosting two of her own prime time television specials in 1969 and 1973. Cass’s wit and jovial determination paid off; she would release five solo albums and a top 40 single “Make Your Own Kind of Music” before her sudden passing in 1974, at a tragically young 32 years old.

Cass Elliot was simply too talented to be ignored. Even the bands that didn’t want her, needed her. She successfully outshined others in an industry that was initially determined to shut her out; moreover, she broke through the harshest barrier – the gaze of the American public – and emerged as a glamourous, magnetic figure of her generation. Everything about Cass was big; her talent, her heart, and her legacy. The Mamas & The Papas have one platinum and two gold albums, six Billboard top-ten singles, and combined sales of over 40 million records worldwide. The group won a Grammy® in 1967 for the song “Monday, Monday” and were welcomed into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2001. Cass was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame posthumously for her role in the Mamas and The Papas in 1998.

Interviews

-

The Rolling Stone Interview

October 26, 1968, No. 20

Repeated reports that the Mamas and the Papas had broken up were at last, it seemed, confirmed. Mama Cass Elliot was going it alone. When I interviewed her- her first interview in more than a year, she said- she had just finished recording her first solo album. She was preparing a nightclub act for Las Vegas (Caesar’s Palace for three weeks, beginning Oct. 14). She was picking and choosing carefully from among the dozens of guest star television invitations. And two networks were bidding for her talents as host of her own weekly variety show. Another Mamas and Papas album- “Farewell to the Last Golden Era, Vol. 2”- was as yet unreleased, but it seemed definite the Mamas and Papas had already said their farewell as a group.

Cass Elliot had sung alone before, in a jazz club in Washington , D.C. (long before joining the Mamas and the Papas), and as a member of two other groups, The Big Three and the Mugwumps. But it was as a member of America’s Fantastic Four, the Mamas and the Papas, that she built her public reputation; in three years, she became the unchallenged queen of the pop music scene. During the same period she became a real mama, developed an avid interest in the “borderline sciences,” and, thanks in large part to the Democratic convention, became a political activist.

These subjects, among others, were discussed with all the emotion they were due in the Beverly Hills office of her personal manager, Bobby Roberts. Cass entered an hour late, apologizing. She is a Virgo and she said that meant she hated to be late, but explained that she had just come from Dunhill Records, where she had heard for the first time a complete playback of her album, “Dream a Little Dream.” We began our talk with that subject.

Jerry Hopkins

Are you pleased with your album?

Well, David Crosby said about a dozen times it took him further than he’d meant to go, which I thought was such a groovy compliment. It’s me. It’s where I’m at. Some friends came in- Graham Nash of the Hollies, John Sebastian- and they said, “I’m gonna have to tell you, if it’s bad, I’m gonna have to tell you, because I really love you and I wouldn’t want you to put something out that you’re gonna be ashamed of.” I said, “If it isn’t great, it’s because I’m not great then. Whatever it is, it’s where I’m at right now.” I think it’s more important what other people think of it.

I guess it’s a lot lower key than a lot of screaming and yelling I did with the Mamas and Papas. It’s not nearly as intense vocally. I think it’s intense emotionally.

The last Mamas and Papas album was lower key than what had preceded it…

I didn’t quite understand that last album. I thought it was overdone. My role in the Mamas and Papas was basically just to sing. John (Phillips) did all the arranging and although there were a lot of things I didn’t really understand, we did them. I will admit in all honesty there are a very few songs on all the Mamas and Papas albums that I’m really proud to listen to. I don’t have the records in my house. Not because I’m a snob. I just don’t feel like listening to them. If somebody comes over and says, “Will you play that for me?” what I do is run over to the record player and play “Shake It Up, Baby” or something, because it offends me. But I don’t think I’ll take my new album off. It’s the first thing I’ve ever done I can listen to objectively. I can listen to the vocals and the orchestra and everything and not be chained just to my own voice in a playback.

Who produced your new album?

I had a great producer, John Simon. I just stumbled on him by luck. I didn’t know anything about him. He had a great sense of humor. As a matter of fact, I thought he was silly and I thought here’s somebody I can really work with because I’m basically the silliest person I know. A friend of mine, Alan Pariser, brought him over for dinner. Alan had played him MUSIC FROM THE BIG PINK. I guess I was too out of it to listen to it because it didn’t make any impression on me whatsoever the first time I heard it. Then I met Simon. I had been looking for six months for the right producer. Because I knew I wasn’t capable of doing it myself; I didn’t have the objectivity. I didn’t want to hire a staff of people: “Ok, you write the strings, and you write the horns, and you write the arrangements, and you play the guitar.” I wanted one person that I could work with and really communicate with, who could understand me and my music and what I wanted to say. So when he came over to the house the next time, I said, “Hey, are you busy?” He said, “No, I’m sort of busy.” He was doing the Electric Flag all the time, and Janis Joplin and whatever else, a movie, but he said, “I’ve got time.” We sort of separated for a few days and thought it over. I went out and got all the albums he’d ever produced- Leonard Cohen, Simon and Garfunkel- and just listened. I said, “Yeah, he’s definitely the right person.” I called him and for about three weeks we hung out and talked, swam in my pool and played with my baby. Then we started to put the material together.

What did you have in mind?

I had a concept for the album. I wanted to do songs that had been written by people I knew, but had never been able to sing because John wrote most of the Mamas and Papas material. People like David Crosby, Graham Nash, John Sebastian. I thought I’d call the album In the Words of My Friends. But we found we needed broader material. As it is, I’ve got a song of Sebastian’s, two songs of John Simon’s, one song of Graham Nash, a song my sister wrote, a song John Hartford wrote, a Leonard Cohen song, and Cyrus Faryar wrote two songs. So it did turn out to be the words of my friends.

Which Mamas and Papas songs do you like?

“No Salt on Her Tail,” “Look Through My Window,” “Monday, Monday,” “Go Where You Want to Go,” “Got a Feeling.” Notice I haven’t mentioned any songs from the last album. I wonder what that is? Maybe because that album was such an arduous task. We spent one whole month on one song, just the vocals for “The Love of Ivy” took one whole month. I did my album in three weeks, a total of ten days in the studio. Live with the band, not prerecorded tracks sitting there with earphones. What a thrill, what a fantastic voyage- as they say in movie land.

What was it that led you to go out as a single? Did you feel the group had run its course as far as you were concerned?

Well, having the baby changed my life a lot. I don’t want to go on the road, you see. It’s actually a matter of economics, much like the Vietnamese war, I guess. I didn’t want to go on the road and I wanted to stay home with my baby. I guess I could go to Kansas and be a waitress and support my child that way. But I’d rather live comfortable and I wanted to do more creative work. I didn’t just want to be part of a group. I wanted to be able to do television, and a movie if it came up, to sort of diversify myself, to extend myself. Within the framework of a group, that freedom is not possible.

We had sort of an unwritten agreement- us all being friends and through all those changes and all- that whenever anybody wanted to quit, they could just quit. So I went to John and said, “Look, it’s been two and a half years and I’m really tired and I want to do some stuff on my own.” He said, “Well, perhaps it wouldn’t be proper for you to do that as a member of the group, so if you want to leave, we’ll understand.”

So then we tried to recapture ourselves in this album. I don’t know whether we successfully made it. I know it hasn’t sold as well. And I can’t help but feel it has a lot to do with the vibrations, vibrations that the music produced- not being as electric and exuberant as we once were.

How does Lou Adler figure in not figuring as producer of you’re album- or is that a touchy subject?

Oh, it’s touchy as hell. I’ll say it like it is. I think Lou felt that if he produced my record it would intensify the alienation of the group. He didn’t want to be responsible for alienating the group from itself. So he respectfully declined my offer. I waited for months for him to make up his mind.

I didn’t feel that I wanted John to produce my album. I wanted it to be Lou or somebody else. This is conjecture on my part, but I think that John felt he wanted to produce it. I just felt for some reason that as soon as I got out of the group, I wanted to be free of every entanglement, creatively.

Do you think a group like the Mamas and Papas would make it today as completely as, say, two or three years ago?

I think the unique thing about music and graphic art is as oposed to, say, acting and directing, that if you are good you can always create a place for yourself. In acting, for instance, there’s only a certain amount of good parts; you have to find the right vehicle. But if you’re making good music, man, there’s so much room. I think that any group that’s really good can make it, anytime. That was my feeling behind the Mamas and Papas. When I heard us sing together the first time… we knew, we KNEW… this is it. This was when we first came to California, after we’d left the islands.

Is that a true story about a pipe falling on your head…

It’s true, I did get hit on the head by a pipe that fell down and my range was increased by three notes. They were tearing this club apart in the islands, revamping it, putting in a dance floor. Workmen dropped a thin metal plumbing pipe and it hit me on the head and knocked me to the ground. I had a concussion and went to the hospital. I had a bad headache for about two weeks and all of a sudden I was singing higher. It’s true. Honest to God.

Do you think the Mamas and Papas might someday re-emerge?

Before I made my album I really believed we’d all get back together someday and do another album. Now I don’t know. There’s something about being a part of a group. You can call it a symbiotic relationship or something you want- that is unique from doing it yourself. But I would love, in all honesty, to do another album with the Mamas and Papas sometime. I miss them.

We’re still friends and we want to be friends. Because you break up a successful group, which is really what I did, you know, there’s some kind of karma here. I don’t feel guilty about it; I left the group because I had to. That was being honest. My mother always told me that if you tell lies, you get in trouble, and if you don’t tell lies, you never get in trouble. Maybe there is some bitterness, but they’re not showing it to me, and I’m not showing it to them. It’s been very gentle.

Did you use backup voices in your album?

On two songs. I sang with the Blossoms and Brenda Holloway. We did some gospel things. Couple of songs I sang with myself. But basically, they’re all solo vocals. Not double-track no over-dub just flat. Me.

Who were the musicians you used?

Oooh, boy. John Simon played piano. Harvey Brooks from the Electric Flag played bass. Paul Harris played piano, too, and organ. James Burton, one of the great guitar players of all time—he played all the Elvis Presley and Ricky Nelson dates—played dobro. Stephen Stills. Cyrus Faryar. Jimmy Gordon on drums. Plas Johnson on sax. This crazy kid named Dino, this crazy Cuban from San Francisco, played conga. And Phil Austin of the Firesign Theatre did some tremendous, fun vocal over-dubs. It was a jovial little crew.

Who’s working with you on the Vegas act?

Mason Williams is gonna write it. Harvey Brooks is putting a band together. What we’re gonna do is… I believe that if you truly dig what you are doing, if you lay it out that way, nobody can not respond. I think my plans are to just build up, not relent for a moment. That’s what rock and roll is. Rock and roll is relentless. That’s what I want to do in Vegas--- not let up. Really pour it on. Have a band. Bring music and entertainment and relaxation and highness and everything else to Vegas. I don’t think it’s ever been done there.

Have you ever been to Vegas?

Well, Harry Belafonte was opening there that night and his opening number was “Rock Island Line.” I sat there and I thought; he’s great, but it’s gotta be 25 years behind what’s happening. I’m gonna float my band above the stage on an inflatable, helium-filled, set. When the curtains open, I want them to go “WHAT???”

I met the bosses of the hotel. They’re paying me an outrageous sum of money; $40,000 a week, which is totally silly. If Emmitt Grogan ever heard about it, I’d really be in deep trouble. Anyway, I caught these owners looking at me as if they were saying: “What the hell is she gonna do?” And I thought to myself: “You just wait… you have no idea… I’m gonna blow your brains out.”

I’m trying to get Mike Bloomfield to play guitar for me. I would just dig to have Michael there. I love Michael. You know, I sang on their record. That’s never really been formally declared. I did the background voicing with Buddy Miles on “Groovin’ Is Easy.” Somebody from San Francisco came down and said, “Hey, have you heard the Electric Flag?” I said no, and they said come to the studio at 10 o’clock in the morning. I said, “You’re crazy; nobody gets me into a studio at 10 o’clock on a Saturday morning, when I just left another studio at three.” But I went, and got so flipped out by the Electric Flag! It’s too bad their first album was recorded so badly--- no presence at all. It’s really too bad, because they were just the greatest group this country has ever seen. Now we’ve got “Big Pink”, and that’s a different bag. The Flag was the first big band rock sound. So I sang with them, although I never admitted it before.

I felt it lost an important element—a vital element--- when Michael left. I dig Jimi Hendrix and think he’s an outasight guitar player. But Michael is intellectual and being white, I respond intellectually. He grabs me. He’s a musician and a technician and intelligent. I think he’s probably the finest guitar player we have.

You put music on at least two levels then… one being intellectual or intellectual as opposed to something else?

No, I don’t put it on levels. I listen to it. If I like it, then later I analyze why I like it. First has to come the initial liking. I can’t say, really. Like, today, I’d rather hear Jimi Hendrix. Today. The Doors, for instance: I can’t really get into their music. I find it very one-dimensional. True, it’s far out. But when you got there finally, it’s just in one. It doesn’t surround me or take me away. Whereas the Beatles always have completely turned me on. With Michael, it’s the same thing. His music is intellectual and being white, like I say, I respond to that side of his music also, in addition to his musical ability and technical knowledge. I respond also to his intellectualism as he approaches his guitar. It’s not “as opposed to,” but in addition to. Michael can play the blues. So can Eric Clapton and so can Jimi Hendrix. But when Michael plays, he takes me very far. He backhands me a little bit more, whereas Jimi Hendrix is right in there, solid, guttural, right there! I think Michael’s approach is more intellectual.

Are there records you listen to more than others?

I listen to “Big Pink” voraciously. It’s happy music. I listen to Dr. John and the Night Tripper. I listen to the Cream, Jimi Hendrix. I listen to Dylan’s last album a lot. I never understood him before. I don’t listen to the new groups much. I don’t listen to Janis Joplin and I don’t listen to Country Joe and the Fish or Steppenwolf, or any of the groups that are making a lot of noise now. I haven’t been able to get in to their music. I listen to music I understand. That’s why I made the comment about Dylan. The last album, John Wesley Harding, turned me on. I loved it and I understood it.

As a solo artist, how are you being billed?

I hope the marquee (in Vegas) just says Cass Elliot. I’m afraid it might say Mama Cass Elliot. It’s a stigma I might not be able to drop right away. I fought it all my folk singing life. Before I was even with the Mamas and Papas. I hated it. Everybody’d say, “Hey, mama, what’s happening?” Then came the Mamas and Papas and I was stuck with it. And now people call me Mama Cass because of the baby. So I don’t know whether I’m gonna be able to really get away from it.

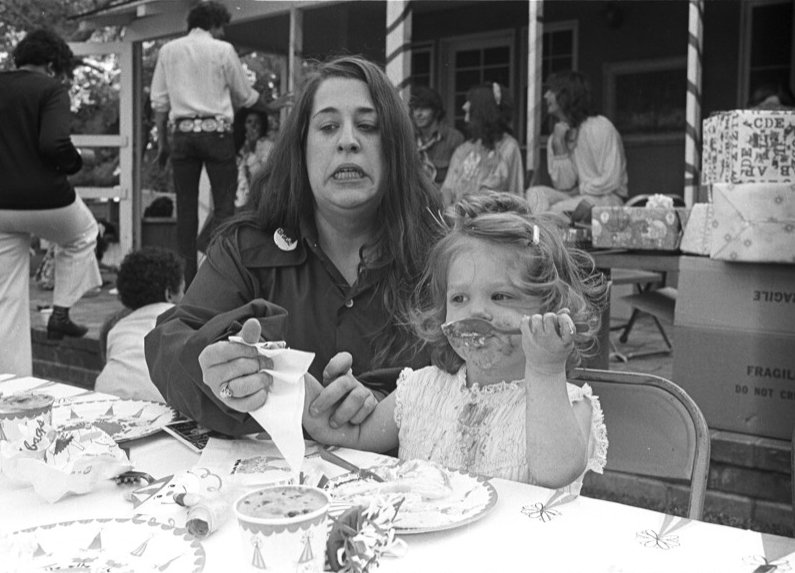

The baby goes with me, by the way. It’s in my contract. You do two shows a day, seven days a week, so it’s like 48 shows straight and I’d never have time to visit her otherwise. She’s just at the right age, 16 months. She plays harmonica and she’s very rhythmical; she dances all the time. An hour a day I put her on my lap and she plays organ. When I was pregnant with her and we were recording the “Deliver” album, I use to put the earphones on my stomach. After she was born and we went to Europe, I left her at my mother’s house for a couple of weeks. My mother told me when I got back that when the baby was unhappy, she’d put on that album and it would soothe her right away. The baby seemed to be familiar with all the songs. It was very relaxing to her. So… that’s my comment on pre-natal influence.

What is your day like, when you aren’t working?

Most of the time I’m at home. I hardly ever go out. I get up early in the day with the baby and my day is her day. At 7:30 I watch the Huntley-Brinkley report, watch a little television, and go to sleep. I’m a member of the Factory- somebody gave me a membership. So occasionally I say to someone, “Hey, you wanna see something?” And we go to the Factory and sit and laugh. I don’t drink, so I’m not one of those people who go from bar to bar.

But you are known as “The Queen of Los Angeles Pop Society.”

Who else is there? Gracie Slick lives in San Francisco . I guess it’s because I know all the people. We’ve been friends for many, many years, and we’ve maintained our relationship. So if you come over to my house and see Eric Clapton and David Crosby and Steve Stills playing guitar together and Buddy Miles walks in, it’s not because I got out my Local 47 book and called up and said let’s get a bunch of musicians together. My house is a very free house. It’s not a crash pad and people don’t come without calling. But on an afternoon, especially weekends, I always get a lot of delicatessen food in, because I know David is going to come over for a swim and things are going to happen. Music happens in my house and that pleases me. Joni Mitchell has written many songs sitting in my living room. Christmas day when we were all having dinner, she was writing songs. It’s a joy for me to have music in my house. It can’t hurt my kid any, either.

At the same time, you are, or have been, very much a part of the public scene, as when you helped open the Kaleidoscope. What is your reaction to that level of what’s going today?

I think it’s silly. Somebody called me up and said, “You wanna come and cut a tape?” And I said, “Why not?” So I called my friends none of whom are in pop music, and said, “Hey, you wanna go on a trip? Let’s go down to the Kaleidoscope and I’ll show you something.” It’s silly. I mean, who am I? What possible value can it have? I mean, if somebody calls you up on the phone five, six, ten times to get you to do something, why not do it? I go some places just because I want to see things. I went to the premiere of Alice B. Toklas because I knew if I didn’t go then, I probably wouldn’t have stood in line to go to the movie. It’s hard to move around in public. Go ahead… ask me what I hate most about my fame… go ahead: What do you hate most about your fame Cass? Say it.

What do you hate most about your fame Cass?

Everything I’ve learned in life I’ve learned either by doing it or watching the changes other people go through. And when you’re famous, you don’t get to meet people--- because they want you to like them when they present themselves to you, present the best sides of themselves, and you don’t see the real people. Which is why I don’t really go anywhere. And when I do, I put on my silly face and do what they expect me to do. Actually, I never do what they expect me to do. It’s the only way I could go on doing what I have to do. I do whatever I… you know, I didn’t even comb my hair today. I didn’t know we were taking pictures but when I found out, it didn’t change my mind any. Interview verite.

There’s a song in my album called “California Earthquake” and the opening line is: “I heard they exploded the underground blast/ What they say is gonna happen is gonna happen at last/ That’s the way it appears/ They tell me the fault line runs right through here/ So that may be, that may be/ What’s gonna happen is gonna happen to me/ That’s the way it appears.” That’s where it’s at. My sister is a part-time clairvoyant. She says “Get the baby out of here; move to Kansas” I say, “Look, I’m here now. There must be a reason I’m here.” If that’s fatalistic, be that as it may. Where my work is, is where my life is, and if we’re falling in the in the ocean, we’re falling into the ocean. The second verse says: “Atlantis will rise/ Sunset Boulevard will fall…” And what could be more timely than that? It’s where it’s at.

David Crosby’s boat is anchored about sixty miles from where this temple is supposed to have risen in the Atlantic . This was reported in the New York Times. Brandon DeWilde’s wife Susan called the New York Times to verify it, and they did. Apparently a temple has been spotted protruding two feet above the surface of the sea in very well sailed waters, near Bimini off the coast of Florida. And it’s supposedly Atlantis. So I said to David, “Let’s go, man; let’s go see.” Because I pride myself on being an old soul and I would say that I’d know if it’s Atlantis. Maybe it’s not Atlantis. Maybe it’s Miami Beach. But let’s go see anyway.

You’ve mentioned astrology, and now Atlantis… and Dunhill uses a horoscope as a biography for you… And as I recall, one of the Mamas and Papas albums included an astrological breakdown of the group. Is this general area important to you?

Well, I would say that there are certain glittering generalities that can be made about every sign that will hold true about everybody who’s a member of that sign. For instance, if you had been a Virgo, you would have understood how I hate to be late. I broke up a group I was in once called The Big Three because one of the guys was chronically late and I couldn’t take it. I feel when you’re supposed to be some place on time, you’re there on time. You don’t hang people up. It doesn’t matter if you’re the President of the United States. That’s not what you are here for, to hang people up. When I know somebody’s sign, and I usually know everybody’s sign whether they tell me or not--- after getting into this for several years--- it helps me to deal with them. Usually I’d rather let people deal with me. That’s a total ego hang up, but that’s where it’s at.

This interest does go back several years, then?

Yeah, I’d say a couple of thousand. Like I said, I think I would recognize Atlantis. I wouldn’t be pretentious enough to try to explain that, though, because there are people who would be offended by it. I think I would be offended by it if somebody said, “Why, I’ll know Atlantis if I see it.” But inside myself I know that, karmically, I would know it if it were Atlantis. I’ve had quite a few experiences like that. I’ll tell you one. I’ve always wanted to go to England; I’ve always felt a tremendous drawing to England--- especially the Elizabethan period. I felt I was familiar with a lot of it--- more than what I was familiar with from what I read and studied in school. I went to England. I started driving. I drove to Stonehenge and found that I had been there. It was familiar to me. I went to the tower of London and knew that I had been there. It was more than just feeling vibrations, which a lot of people can do--- feel, you know, vibrations of a place that has antiquity screaming through it. It was an irrefutable fact. It was like coming home for me.

Reincarnation isn’t such a far-out theory, after all. I had a medium who did a karmic reading of my soul. She went into a trance and spoke to me in a completely different voice from her own. I’m a diehard skeptic, but she told me that Owen, my daughter, had been my child before and that her soul had been returned to me. I thought that was a lovely thought, even if it’s not true. And even her name, Owen, which is a peculiar name to name a girl child, it’s a peaceful sound to me. I don’t think it has anything to do with Om, although they’re all the same, all the soft sounds. She’s a very soft sound.

I spent some time with Rick Griffin and his wife and baby, Flaven. And they’re all the same, all those babies. I took acid five times when I was pregnant. I don’t believe in this chromosomal damage. I think it’s all hogwash; it’s all a vicious plot by the establishment. I was told all the things I couldn’t do when I was pregnant, and I did them all. Because, you know instinctively what you can do. I took psychedelics. I didn’t feel that I had hurt her in any way. As a matter of fact, it was on an acid trip that I realized that I was pregnant--- and I was about three weeks pregnant.

What did you mean when you said “all these babies are alike?”

Babies of hippies have gotta be different from other babies--- just by virtue of the fact that they are totally unrestricted. I think that hippies are more enlightened and therefore tend to be a lot freer with their children. Let’s put it this way: the kids I went to high school with, well, I’ve seen their children. Now… my contemporaries… they are not the people I went to high school and college with… they are in the creative forces… and their children are different. And they are different because of their parents. And what they are allowed to do and say. Flaven’s a beautiful child. I’ve heard that story about kids are high naturally, but I’ve seen kids that aren’t high, kids who’ve had the high taken out of them. That’s why I say those babies are all alike; like us mothers.

I hope these babies have a world to live in. I hope they have a place to go, a land to walk on. I remember when I was ten years old, in Washington, D.C., and I lived with fear of the atom bomb that would keep me awake nights and make me wake up screaming. I used to babysit for my younger brother and sister and I’d be terrified if I heard a siren, a police car, or an ambulance. I’d say, “My God, what if this is it! How do I protect them?” We used to have duck-and-cover exercises in school, where they’d ring a bell at any time of the day, sometimes five or six times a day, and we’d crawl under our desks and put our hands like this to protect the back of our necks from the bomb. We all carried that with us.

I think everybody who has a brain should get involved in politics. Working within. Not criticizing it from the outside. Become an active participant, no matter how feeble you think the effort is. I saw in that Democratic convention in Chicago that it was not feeble. There were more people interested in what I was interested in than I believed possible. I saw people crying because the minority plank on Vietnam was defeated in the platform. And I thought: Thank God! All right, so we didn’t get it, but thank God there are some people in there now, in the establishment, who want to change it. So let everybody be active. That’s what I dig about Paul Krassner, man.

I heard he will be writing the liner notes for your album.

Yes, he is. I’ve known him for many, many years. I met him with Timothy Leary and I fell instantly in love with his entire mind and body, and I would do anything for him. He’s a hopeless idealist. I asked him to write my liner notes and he was delighted. He asked me what to write. I said write about the Yippies or write about anything; just write what you would like people to read, it doesn’t have to do with the album.

Do you think the Democratic convention and what happened in Chicago really changed many heads?

Oh, yeah. Let me talk about the head it changed in me. It made me want to work, made me feel my opinions and ideas were not futile, that there would be room in an organized movement of politics for me to voice myself and change things.

I was asked to participate in Bobby Kennedy’s campaign. I thought about McCarthy and I realized I thought McCarthy was a little too lyrical, but I agreed with his ideas. I felt much stronger about McGovern; I don’t know why. But I didn’t participate in any way, for anyone. I was just a voyeur and watched it--- to see tragedy heaped upon tragedy.

I’d say I’m gonna be active. I’m gonna do everything I can. Whatever it is, and I’m sure there are people who know what it is, and they’ll tell me. I’m guilty of the sin of omission as much as anybody else. I never spoke up.

When I was in Vegas I saw Harry Belafonte, I wanted to talk to him. I said, “Tell me what to do about fear.” He asked me what I was afraid of. I said, “I don’t believe what those other people believe and I don’t want to have to pay dues for things that I never said and things that I never felt. Tell me what to do when Roosevelt Grier comes running down my driveway to burn down my house. How do I run outside and say, “Hey, man, I never said nigger and my kid’s never gonna say nigger.” That’s my fear--- the white, liberal fear. How do you tell them that you’re on their side? Which is a bigoted way of expressing it--- implying there are sides. Belafonte was very moved. He just reached out and took my hand and squeezed it. He didn’t say anything, he just looked at me for a long time.

Will you be campaigning now?

Yeah, on all levels. I’d like to see Paul Krassner get in. I think he could change the minds of a lot of people.

My philosophy is I’m gonna fight as hard as I can to keep all the bad things from happening. But if they are gonna happen and I happen to be in the city where they are happening--- like in the song, “California Earthquake”--- then there’s not much I can do about it. I can’t uproot my whole life, just because I have a feeling that things may not work out all right. There’s also always the chance that everything is going to be just swell, guys. Just hang in there. But I don’t think it can happen on it’s own.

I think the most successful way to overthrow any government is through infiltration. It’s been proven for years. The dream, of course, is that there is going to be a fantastic cataclysm, and that tomorrow we have Adlai Stevenson in the White House. That’s not going to happen, and not because Adlai Stevenson is dead. The reason it’s not going to happen is that kind of overthrow is not possible. So I will work in the only way I know how, and that is within the establishment--- because that is the only existing program. Let someone come up with another one and if it’s good I’d do it in a second.

I know very few who are willing to die for their convictions. I wouldn’t be hit on the head with a billy club or have mace squirted in my face. When I was younger and a radical at American University maybe… as a matter of fact, I was at the march on the Pentagon just last year, right in the front taking pictures, just being there to find out what was happening, and I was knocked down and stepped on. I don’t want to do that again. It didn’t accomplish anything. They lied about everything that happened. Everything in the newspapers were just lies. There were 100,000 people there, not 15,000. And it was very orderly, very well organized. They just did not tell the truth. Look, like it or not, Chicago was the truth, and all America saw it.

How important do you feel pop music is in all this?

Well, look what it’s done so far. How can you negate the fact that it has mass appeal? It gets into millions of homes and lives. Like this song Spanky and Our Gang recorded. It turns me on so much when they sing; “And if I can make you give a damn/ about your fellow man…” Let’s take the people who have latent thoughts about maybe the United States isn’t always right. They hear a song like “Give a Damn” and maybe it’ll awaken them. If it makes you cross that bridge between apathy and effective participation, that’s great. There’s so much talk about the Drug Generation and songs about drugs. That’s stupid. They aren’t songs about drugs; they’re about life. Music can play a huge part, because it’s the international communicative force.

Do you feel music should make social comment, then?

I feel that it can, and whenever possible, when they have something to say, it should be heard. I wouldn’t say it has to. I wouldn’t go up to the Quicksilver Messenger Service and say, “Hey, you guys ought to do a protest song because people listen to you and you’re in a position of influence and you should do something about it.” Yet, I do believe that. If you are in a position of influence, you should do something about it. Not necessarily inflict your opinion on other people, but if you really think you’re right, you should tell it.

Does some of the material on your album reflect this attitude?

“California Earthquake” does. There’s another called “Sweet Believer”, which I feel… it’s still so fresh and new to me, it’s hard to say. All the songs mean something. They’re not political. I must admit I didn’t think of politics when I started the album. I was thinking “Who am I?” And “How do I tell people out there who I am?” Not being a writer, the only way is to sing songs that reflect my opinions.

The album was also conceived and put together before the Democratic convention.

Yes, but we had politics before we had the convention, didn’t we?

Yes, but wasn’t it at that point your head changed around some?

Nah. It changed around when John Kennedy was killed. When John Kennedy was killed, I really became frightened. I said: How can they do that, how can they do that… snuff out the white hope? And then Martin Luther King. You know the list. And many people that we didn’t know. And that kid, the Black Panther who was shot down with his hands over his head, Bobby Hutton. I didn’t even know him. But I didn’t have to know him to know it was wrong. He may have been anything. He may even have been a bad person, or a rapist, or a walking hallucinogenic drug, or anything. But he didn’t have to die.

I’ve always been so apathetic. I figured okay, maybe the world is going to fall down around me. Now I feel… maybe that’s motherhood, too. I want to make a better world, I want to make sure she has some place to walk around.

What do you think you’ll be doing?

I hope they don’t ask me to sing. But if that’s what they want me to do, if that’s what I can do, I’ll do it.

-

Sink Along with Mama Cass

By William Kloman

June, 1969

The road through Laurel Canyon rises from a small country store where dreamy young couples smile at one another across the apple bins. It rises, past the house where Tom Mix's wonder horse Tony is buried under the living room floor, and up past the rubble of Harry Houdini's mansion, which attracts pre-teen hippies, who picnic there on Twinkies and Fresca. Above the picnic ground, the homes of record industry company freaks cling to cliffs by spidery beams and willpower. Police helicopters chop overhead, alert for signs of psychedelic vegetation drying on the rooftops. Inside the houses, small families wait for the Earthquake. Come the Revolution, they tell you, Laurel Canyon will be the new Warsaw Ghetto.

The road goes up until it joins Mulholland Drive, where people used to go to park and neck, before the Pill, when girls lost their virginity in borrowed cars. The Tonight Show audience always laughs appreciatively when Johnny mentions the Drive. It recalls the Arcadian joys of whisky highs and guileless contraception.

From Mulholland Drive, the alert traveler can glimpse an overgrown Victorian rose garden nuzzling against a grand stone cottage. It is the sort of house Bo-peep might have designed for herself if she had ever struck it rich. An egg-yolk yellow Aston Martin stands idle under a carport jutting from the cottage. The front yard is littered with a child's toys.

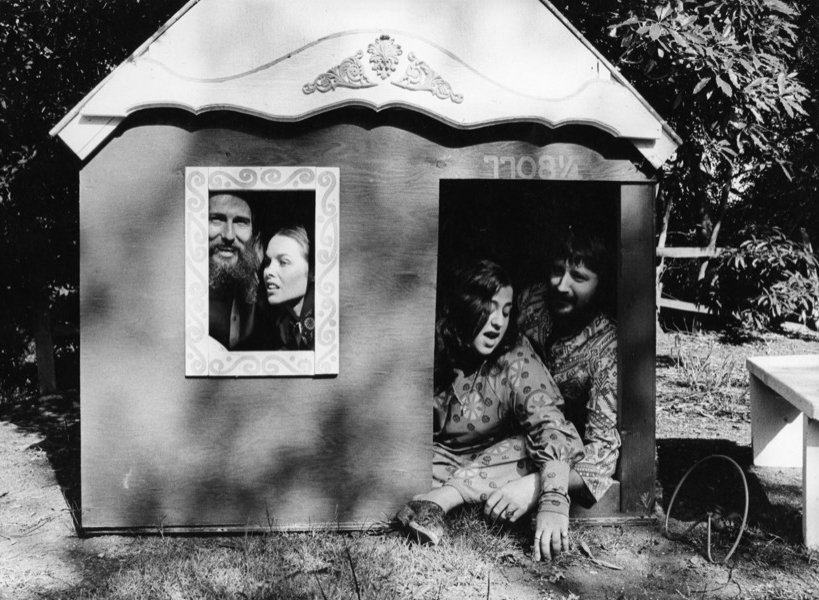

A horn blows in the cottage driveway and a tangle of dark blonde hair flounces from a gabled window overhead. Hair, house, and roses belong to Cass Elliot. So does the James Bond sports car and the baby who owns the toys. The toys are those of Owen Vanessa, Mama Cass Elliot's little baby girl. Mama Cass is the chubby girl who used to sing all those hefty mezzo-soprano parts with the Mamas and the Papas. She has broken with the other Mamas and Papas, and is off to become a big star of her own.

Now between jobs, Mama Cass reigns as superstar, earth mother, and legendary queen of all the hippies in the canyon below. As we join Mama Cass, she is visited by her sister Leah - the cause of the blowing horn - who is preggers, and who has a pain. Leah stands in the garden below, looking up. "Drink a glass of milk and go to bed," Cass says from her window. "Warm it first, then get in bed and drink it." Leah goes away, content, and Cass withdraws. The interior of the cottage belies its pastoral exterior by closely resembling an East Village crash pad.

"My sister is prenatal," Cass says, padding through a tangle of clothing and ostrich feathers. Framed gold records, mementos of Cass' glory days with the Mamas and the Papas - line the floorboards, unhung. "I wish I was prenatal again. Oh, well." Cass climbs into bed. Her aspect is glum. Her hair - soft and stringy like that of a small girl - catches the morning sunlight as Cass fluffs a pillow and gently clears her throat. The bed is massive, canopied, draped in golden velvet. Carved wooden panels supporting the canopy are crowded with arcane fertility symbols: birds of paradise, thin elephants, exotic vegetation.

In bed with Cass is a telephone, an ashtray, cigarettes, magazines, books, a box of Kleenex. Perhaps there is a picture of Little Lulu on the Kleenex box, and perhaps not. On a shelf at the foot of the bed, inside the velvet curtains, there is definitely a television set, more magazines, and an assortment of pills (big reds, little yellows) that would cause Jacqueline Susann to weep for joy. The scene is one of convalescence. Cass has tonsillitis. For a week now, the Hollywood trade papers have been following the progress of her illness with enthusiasm. Daily Medical bulletins have appeared in all the gossip columns. Some say mononucleosis. Some say hepatitis. Some say hemorrhaging. Some do not. The columnists have begun to call her Miss Cass because she gave up her last name when she went to Las Vegas billed as plain Mama Cass, lost her voice, and bombed.

The disaster in Las Vegas was heroic in proportion, epic in scope, and becomes even grander in the retelling. Cass opened and closed on the very same night - the first night of what was to have been a three week engagement at Caesars Palace. Billboards throughout the Westlands herald the swank resort. "There is only one Palace," the billboards say. It may look like a giant concrete nutmeg grater plunked mid-desert. It may blend Hellenic, Hellenistic, and Roman decor with mad abandon.

It may even - as detractors claim - be the terminal vulgarity of the modern age. But show business-wise, Caesars Palace is the top of the heap. Mama Cass Elliot chose the Palace for her first encounter with a live audience since her split from the Mamas and Papas partly because of its grandeur, partly because her salary would be $40,000 a week, and partly because she knew four Mexican boys who worked there. Now she was resting her voice and considering her comeback. It would be the first time in entertainment history that a performer would make a comeback after only one night of stardom. Such things used to take decades.

Several distinct varieties of comeback were available at this point. There was the Judy Garland, which was dazzlingly traumatic but somehow threadbare. There was the Kate Smith, but that involved years of waiting, and who could tell if today's audience had that kind of patience. There was the Helen Morgan comeback, which required an abandoned nightclub and hundreds of extras to cheer and cry. And there was the Shirley Temple, which meant hiding out long enough to work up a new kind of act. None of these would do.

Some people had said that the Las Vegas opening itself was not unlike a comeback.

Cass's personal manager, Bobby Roberts, a former tap dancer who also guided Ann Margaret's career, had been the first to identify the odd atmosphere of the opening night. When it became clear that the act was falling apart - clear that Cass should never have been permitted to go on stage to begin with - Roberts had whispered to friends, amid sniffs of nervous laughter, "It's just like watching a comeback. Watching a big star's comeback, watching Cass UP there is."

Cass is out of bed, restless. She is standing in front of her gabled window, barefoot and in a quilted dressing gown. The rosebushes at the far end of the yard have withered and gone to seed. Some months before, the man who lives across the road had come down his hill to tell Cass that the rosebushes were on his property, not hers. Cass has not tended the rosebushes since that day, devoting her attention instead to a small patch of artichokes on the opposite side of the house. Friends who have eaten Cass's artichokes claim that they are the best artichokes in California, with the possible exception of the artichokes grown by the Mafia in the Salinas Valley.

The previous night Cass had consoled herself by walking around barefoot in her new sable coat. The coat was a gift from Cass to herself, a token of impending stardom as a single. Cass could no longer afford sable, so the coat would have to go. Cass was miserable. Friends who dropped in for the evening teased her, making reference to things like Sunset Boulevard which added considerably to Cass's misery. She had taken the fur coat off and walked on it, wiggling her toes among the pelts. She had gone upstairs and spread it on her bed and patted it smooth. Then she rolled around on it and began to cry.

"I don't think I have to have my hand slapped that much that they'd take away my coat," she is saying, looking out at the ratty rosebushes. "All I did was get tonsillitis. The worst possible thing happened at the worst possible time." She begins to form a syllogism - a natural tendency for Virgos under stress - then wipes her eyes with a Kleenex. "The worst possible," she says. "What a good premise. It's so reassuring." Then she turns and smiles. "I consider myself now second only to Paul Krassner in tying totally unrelated facts together to form a conspiracy. I'm convinced that I'm the helpless victim of a terrible plot. For weeks somebody has been slipping something into my Chemex coffeepot to cause damage to my pipes at the worst possible time." She climbs back onto the bed. "I'm glad that's all cleared up. For a while there I thought I had bombed 'on purpose." Or perhaps it was the Mafia, trying to turn off Cass's artichokes. It was hard to tell.

The Caesars Palace fling had indeed been costly to Cass. Estimates of the cost ran as high as $90,000. Singers, musicians, sound men, lighting men, all wanted to be paid. Cass had spent $10,000 on the script for the show alone. It was written by Mason Williams, a Smothers Brothers writer who commands high fees. Cass had read the script once and discarded most of it because she decided that she didn't want somebody else's words getting between her and her audience. Cass's intention had been to flatten the audience with sincerity and love, to turn them on to honesty and, in her own words, "blow their minds." In spite of the fact that even old troupers refuse to play Vegas without weeks of meticulous rehearsal, Cass had not managed to stage a fun run-through of her show by opening night. "When I hear my music, it will an come together," she had said repeatedly.

Cass had prepared for Las Vegas by spending three weeks in bed with nervous flutters, punctuated by attacks of nausea and stomach cramps. While Cass was dealing with her vapors, a show had been put together. Harvey Brooks, a highly talented bass player from the defunct Electric Flag, had assembled a six-man rock band to back Cass. To back the rock band, a twenty-piece house orchestra was added in Las Vegas.

A psychedelic lighting expert was flown in from San Francisco. He found the Palace lighting system equipped for Virgin Mary apparitions but short on jazzy effects. A production supervisor was hired to coordinate the various elements, and he brought with him a female rhythm trio called the Sweet Things to add a gloss of soulful pizzazz.

Cass' own contribution was the quartet of sequined Mexicans - Los Hermanos Castro - whom she had once seen on television, and with whom she had immediately fallen in love.

The Castro brothers had, in fact, been me determining factor in Cass's decision to play Las Vegas. When Cass had seen them on the Joey Bishop Show they were appearing in Nero's Nook, a small lounge off the Caesars Palace casino where the "Bottoms Up" revue gives the hotel's patrons a mid-afternoon respite from gambling, much as tea does for British sportsmen. Cass had gone directly to Las Vegas to meet the Castros in person. They told her they had long dreamed of playing the Big Room - the Circus Maximus - so Cass signed them to appear in a show in which she would star, In the Big Room. The yellow James Bond car would have to go. Definitely the sable coat (that was the worst of it). There was a $5000 wristwatch and a $1200 pair of earrings being held at Tiffany's in New York which would have to be canceled. Maybe the Bo-peep house would have to go too. That would come as a shock to the hangers-on - the lovable, scruffy hippie-types who hung out at Cass' pad, drying their socks in Cass' bathroom and making cheery vats of Cream of Wheat in her kitchen on rainy afternoons. Maybe they would have to go.

In the three years Cass had spent with the Mamas and Papas,. the single most successful musical group in America at the time, she had lost whatever habits of economy she ever had. The Mamas and Papas had worked and lived as if there were no tomorrow. They zipped around the country in Lear jets, bought houses and cars with abandon, put up at the best hotels, and carried an entourage of fifteen. Cass, for her part, had loved every minute of it, down to the ennui big stars were expected to affect in the presence of luxury.

In many cities, Cass stepped wearily from limousines, smiling indulgently at hotel doormen. "It is my fate," she sometimes said, "to be constantly dependent upon the generosity of strangers." Perhaps her finest moment came in Carnegie Hall. She had just introduced John Phillips as "the man without whose help I'd still be making beer commercials." When she sat on the apron of the Carnegie Hall stage to sing I Call Your Name, the house went wild. You would have thought Judy Garland had just told them a love secret.

With Denny Doherty, John and Michelle Phillips - the other three Mamas and Papas - Cass Elliot became a celebrity, which means that fame suddenly transcended talent and existed independently of their ability to perform. They’d appeared on the covers of national magazines. They drew crowds wherever they went.

Cass was the most visible member of the group, and her voice the most distinctive, so she became the biggest celebrity. Wherever the group appeared, little fat girls would seek Cass out, ask her advice on their careers, and sit at her feet talking about life. Cass was loved more than the others, perhaps because her people had the greatest needs. What Streisand did for Jewish girls in Brooklyn, Cass Elliot was doing for fat girls everywhere. The diet food people must have hated her the way nose surgeons are said to hate Streisand. While the Mamas and Papas were defining a lifestyle for their fans to emulate, Cass was redefining the concept of beauty among the young.

While Warhol was trying to decide whether Cass or the boys would be more effective nude, Cass withdrew from the venture on the advice of her agents. They were - concerned about what such exposure would do for her image.

In the meantime, Cass posed for photographer Jerry Schatzberg, and the resulting picture was featured as the centerfold of the first edition of Cheetah, a rock magazine that died after eight issues. Cass appeared mother - naked and tattooed, sprawled on a field of daisies. Nobody blamed the Schatzberg photo for Cheetah's collapse, but there was general agreement that editorial taste had not been one of the magazine's strong points.

"I don't know why I wanted a sable to begin with," Cass is saying. "I just always have. Ever since I was eight years old there has never been a time I didn't want a sable coat. I never wanted a mink coat or anything. I just always wanted a sable coat. It was probably some popular song at the time, 'Have to buy me diamonds and pearls, champagne and sables and such.' I just always equated it with the pinnacle of. . . . It was so soft and groovy.

Now I have to give it back." Cass pads around the room, gloomy and distracted. She hums a snatch of song, and shakes her head. "That is show business, man," she says at last.

"You never know what's going to happen. It is the least pre - informative of all businesses. I just don't want to have to make a comeback now. That's so ridiculous. I should have stayed in Baltimore and gone to Goucher and become a teacher or something. You don't just give up your entire life and go into show business. It's too much of a luxury. A luxury, man."

"Why, then, did you…?" The question, scarcely begun, hangs in the still air like a smoke ring. Cass waves it aside lightly, climbs back into bed, and lights a cigarette. "The story of my life," she says. "Random House wants it too."

Mama Cass Elliot - her name was Naomi Cohen in those early days - spent her little girlhood shuttling back and forth between Alexandria, Virginia, and Baltimore, following the flickering star of her father's business schemes. She recalls at least ten instances of bankruptcy during her formative years, but considered her lot infinitely preferable to that of her playmates, most of whose daddies were in the dreary old Army and carried their lunches in brown bags to the Pentagon every morning.

Cass likes to describe her family's situation as "groovy lower - middle - class." When she was eleven, Cass found a consoling object of identification in Carroll Baker's portrayal - in The Miracle - of the hot little novice who leaves her convent to run away with a passing tribe of Spanish gypsies. In the film, the Virgin Mary descends to take Carroll Baker's place in the nunnery, scrubbing floors for her and such, while the young postulant dances the nights away with her dark lover. Cass's first response to the movie was an overwhelming desire to convert to Catholicism, perhaps sensing that the Virgin Mary didn't go around scrubbing floors for Jewish girls.

When Cass reached high' school, her father hit upon a business idea which worked.

He bought a retired public transit bus, equipped it with ultramodern stainless - steel kitchen fixtures, and parked it beside a busy construction site. The restaurant - on - wheels venture was so profitable that the Gohens soon had a fleet of five converted buses doing business at five different construction locations.

Cass' task in the venture was to get up at four - thirty every morning and drive around with her father, cooking breakfast for his customers. In the winter, Cass recalls, her father would have to bang on the buses to scare away the rats and mice which had crept inside to sleep before Cass could go in to start the oatmeal cooking.

At seven - thirty, the workmen sent off to their jobs, Cass would change into her school togs and drive to class, which she found desperately dull compared to the gruff repartee of her father's breakfast trade. Cass still looks back on her restaurant days with fondness. "Meals on Wheels for Schlemiels," she says nostalgically.

"What a life Naomi had." The Cohens' peripatetic ways cost Naomi half an academic credit toward the end of her high - school career. The family had moved to Baltimore, and Cass struggled with night courses in French to make up the missing half credit. After class - it was summertime - she would drive to the Owings Mills Playhouse, where a girl friend was a summer - stock apprentice. The Boy Friend was at the end of a successful run, which the producers wanted to extend. The girl playing the French maid, however, had other commitments, so Cass's friend suggested Cass for the part. Pointing to Cass one evening, she had said: "She can sing!" "I said absolutely not," Cass says, beating her pillow for emphasis. "I had braces on my teeth and everything. Anyway that was my theatrical debut, singing It's Nicer, Much Nicer In Nice, and I was very good. I still remember that song." She lifts her hands and makes floating motions. "They say it's lovely when - a / Young lady's in Vienna / But it's nicer, much nicer. . . .' Oh, it was so sophisticated," she says.

After being the French maid in The Boy Friend, school was out of the question, so Cass stopped going. Instead, she took a part - time job on the society desk of the Baltimore Jewish Times. Cass's job was to layout the magazine section of the paper and to write obituaries. If she weren't actually cheek - to - cheek with the sophisticates of Baltimore Jewish society, she was close. A long shot closer than when she was slinging hash for bricklayers from the back of a bus.

A weekend visit to New York City was enough to convince Cass that she had to try for the Big Time, or regret it forever after. Back in Baltimore, the Cohens flatly refused to indulge their daughter's theatrical impulses, and insisted that she continue her education at Goucher College as soon as she made up the missing half credit.

"They always had great aspirations for me intellectually," Cass says. Crestfallen, Cass quit her job with the Jewish Times, moped around the house for a while, then went to work for the Baltimore Sun, partly to convince her parents that she wasn't a vegetable. Cass's new position called for her to spend her day taking classified ads over the telephone. The whole idea was a bit much, but Cass managed to avoid taking too many ads by chatting all day with her friends, whom she called on the "out" line. When she was fired for clogging the switchboard with personal calls, her parents agreed that maybe New York was the place for their daughter, after all.

Cass packed the family car with clothing and small appliances, and headed for the city. Once there, she parked the car in front of an aunt's house and went in to make a telephone call. She returned a few minutes later to find that all her belongings had been stolen.

"You see, I was just a bumpkin. Just a country bumpkin," Cass explains. "I had just come in to New York from Virginia. Or was it Baltimore?" Cass then began acting classes at a small theatre workshop.

Downstairs, a doorbell rings. Voices are heard. A door opens. More voices. The door shuts.

"Irma," Cass calls hoarsely. "J Que 'Pasa?" She listens but there is no answer. "I think it's my divorce papers. They were due today. They're going to freeze my tonsils out, so I won't have any actual tonsils to show people, but if they were going to cut them out, I wanted to have them made into earrings - bronzed or something.

I think it would be a nice gesture on my part. I could go out on stage and say, 'Here they are, folks.' I want everything to be out front. I'm very worried about my reputation in this business - of always being on time and doing my job, and the whole thing.

Now it's all balown, man, I don't care what anybody tells me about how many people are on my side. I don't want to know how many people are on my side. I want people to understand and believe what went down in Las Vegas and be forgiving. I don't want to. have this tremendous guilt that I've let everybody down." Cass struggled along in New York, a fast montage of making rounds of agents, having pictures taken, and reporting for auditions. She used Glitter and Be Gay, from Candide, as her audition number. Cass also directed a play at the Cafe La Mama, and came close to getting the part of Miss Marmelstein in I Can Get It For You Wholesale, the role which launched Barbra Streisand's career.

"I was led to believe by my agent that there were only three of us up for the part: Streisand, myself, and Zohra Lampert. She's the girl Warren marries in Splendor in the Grass, and probably one of the great undiscovered talents of our. . . so relaxed. Streisand was in another show, and David Merrick wanted her for the Miss Marmelstein part. Miraculously, Barbra's show closed just in time for me not to have signed any contracts. Talent is talent, man. Barbra Streisand is a unique talent. I just don't think we both should have come on at the same time. But it's funny. Miss Streisand and myself both have something to overcome. I don't want to always be Mama Cass, and I'm sure she doesn't always want to be the image people have of her now. I'm sure the movie of Funny Girl will change all that for her. I understand it's gorgeous." After completing a tour with The Music Man, Cass decided to go to college to get a good foundation in drama before attacking the Big Time once more.

"So I went to American University in Washington, and I enrolled. I was twenty - one. I'd been out in the world and doing my thing, and here I was a freshman - a provisional one because I didn't have my high - school diploma - with all these seventeenyear - olds, all dewy - eyed about the theatre. Dewy - eyed I wasn't. I tried staying away from the university theatre, and after six weeks I was hanging around the theatre. I had been in Broadway houses, and I was back on the college level, and it came easy. There was this one young professor who really turned me on. Man, I dug him, and I was one of the worldly compared to the other girls in his class. I'd love to see him. I know we'd still like each other.

"Anyway, I got interested in the theatre and started hanging around with some guys. Then we had the Cuban missile crisis. Remember the Cuban missile crisis? Well, I remember it mostly because American University is a very political school, and everybody was sitting around instead of going to classes. American University is kind of like Berkeley. It gets pretty radical there at times.

Not many people know that. So we were all sitting around wondering what was going to happen - whether we were going to get bombed or what was going to go down. That day when nobody knew what was going to happen? And I met some people, and through them I met this guy, who said, 'Hey, you can really sing good. Why don't you come to Chicago and we can sing?' So I said okay, and I took some money and bought a Volkswagen and we went to Chicago and we formed a group. That's when I first started singing for my career. We spent a horrible, miserable, starving winter in Chicago." Cass is shouting. "Putting it together. Singing. Learning songs. Twenty - five below zero. It was one of the roughest winters they ever had in Chicago. Hmm."

In Omaha, Nebraska, the composition of Cass's traveling group changed. One young singer - Jim Hendricks - was added, and another was dropped. Cass later married Hendricks, at a time when he would have been drafted had he remained single. The divorce is pending.

Hendricks and his girl friend, Vanessa, were at Cass's opening in Las Vegas. Friends say that Cass is so fond of her husband and his girl friend that she named her own daughter Owen Vanessa in her honor. Cass says Hendricks is not Owen's daddy. Some people believe that Cass produced the child by sheer willpower. Others hold that the fertilizing agent remains a mystery to Cass herself. Reporters for classy magazines don't ask their subjects questions about such matters.

In those early days of pop culture (before rock, and near the end of folk unless you want to count Dylan's latest stuff), small bands of singers with non - electric guitars crisscrossed the country, singing for college audiences in off - campus coffee houses where the biggest high you could get was from chewing on the cinnamon stick that you got with your Cappuccino. In one of these houses, Cass met Denny Doherty, who was on the road singing with Zalman Yanovsky. Cass fell immediately in love with Doherty and his glorious golden tenor voice.

Denny can be assumed to have responded with his gruff, thrifty, Canadian Northwoodsman, tender silence.

Cass and Denny kept in touch by telephone while their respective groups were on tour. In mid - 1965, both groups broke up, so Cass and Denny formed a group with Yanovsky and Hendricks, which was billed as Cass Elliot and the Big Three. A Clrummer was added to the group, and its name was changed to the Mugwumps. The Mugwumps cut a record for Warner Brothers, and lasted until the end of the year, at which point Yanovsky and John Sebastian (who had been signed on as a sideman to play harmonica) split to form the Lovin' Spoonful.

Doherty went off to join John Phillips on the island of St. John in the Caribbean, where John and Michelle had gone after their landlord on East Tenth Street auctioned off all their worldly goods to make up for overdue rent. On St. John, Denny, John and Michelle (with a few other Village dropouts) lived in tents, slept on the beach, experimented with LSD, and sang together a lot.

Cass returned to Washington, D.C., where she worked for a while as a single in a small Georgetown club. Then she joined her friends (the folk people all knew one another from the Village) in the Virgin Islands. Cass waited tables in the Islands but didn't have a high enough vocal range to work into the music Phillips was writing with the aid of acid. One day, while Cass was poking about on a construction site on St. Thomas, a workman dropped a thin chunk of pipe on Cass's head. When the headache went away she discovered that her upper register had been increased by three notes. Thus, not unlike the Pallas Athena, who leaped full - blown from the head of godly Zeus, the Mamas and Papas were born, emigrated to California, became the nation's top new singing group, and grew rich and famous beyond the dreams of avarice.

From the highway, Caesars Palace does indeed resemble a giant concrete nutmeg grater. Vast pools and fountains gurgle and play near its entrance, drenching guests on windy days. Approach to the Palace is made by way of a mammoth landscaped parking lot, the greenness of whose jutting lawn seems an obscene gesture of defiance thrust into the desert's crusty face. The sun shines fiercely on the outside.

Within, the air is kept fresh by giant machines hidden in the ceilings. There are no clocks; there is no day or night.

The noise of gambling in the great casino - it is, in fact, the hotel's lobby - seems like the din of a passing train.

Here gaming is pursued more as religion than as sport. Women past their prime gravitate to the machines, insert their coins from paper cups, and pray the gods of fortune will compensate the losses of a lifetime in cold, hard cash. The men are more covert in their play. They throw their dice and turn their cards with practiced nonchalance, the way Clark Gable would.

They page one another on lobby phones, and sign their bar bills with sweeping strokes. When they urinate, they do so in marble toilets marked Caesars. Their ladies repair their eyes in powder rooms labeled Cleopatras.

The place has style.

Cass and her troupe arrived on a Saturday, to allow time to "shake the bugs out of the show" before the Monday opening. The Saturday - afternoon rehearsal had not been much, but Mama Cass - no one in Las Vegas ever called her anything else - had made a good impression in the Noshorium, the hotel coffee shop, joshing with the help and signing autographs. Waitresses, particularly, wanted her signature, usually for their daughters.

"My little girl just loves you, Mama Cass," they would say in their tight Lady Bird twangs. "She even has your record. Plays it all the time. I think it's near wore out," "Buy her a new one," Cass would say.

Sunday evening, Cass appeared briefly at a makeshift rehearsal hall to skim through a medley she planned to sing with the Castro. brothers, then disappeared down a long corridor with two Castros on either arm. The Harvey Brooks ensemble played late into the night, until their sound was tight and hard. The musicians were happy with their sound, but their misgivings about the star of the show gave an early warning of trouble.

"One thing I don't want to do, man," one of them said on Sunday, "is to carry Mama Cass. It's her show, if you know what I mean."

A full rehearsal was called for Monday afternoon, in the Circus Maximus.

As the house staff prepared the Big Room for the dinner show, the twentypiece house orchestra arrived, as did a battered honky - tonk piano which had been shipped at great expense from Los Angeles to add sixteen bars of old - time funk to the middle of one song. Cass appeared in cable - stitch white wool knee socks (no shoes), Polaroid shades, and her custom - made sable coat. She worked out a few numbers, squeezed a Castro or two, discarded what little was left of her $10,000 script, and noticed that her voice was going scratchy.

"Honesty is all you need," she said.

"This show will blow their minds." Celebrities arrived for the opening throughout the afternoon. Peter Lawford and Sammy Davis Jr. were rumored to be on the premises. "Peter said he was coming for the opening," Cass observed, "and I guess he brought Sammy with him." While Cass was putting it together in the Big Room, John and Michelle Phillips were working their way through the lobby, dropping money into various games of chance on their way to their suite. The day before, they had decided to fly to Vegas from Los Angeles to watch Cass strike out on her own. Denny Doherty had planned to come, but cancelled his reservation at the last minute.

Having negotiated the lobby, John and Michelle came upon a large bank of floral tributes waiting to be delivered to Mama Cass's dressing room.

There was a basket from Joan Baez, who was in Nashville making an album, a bunch from Mia Farrow, who was in New Orleans, and a used sledgehammer sent by Tommy Smothers.

Michelle found a spray of American Beauty roses which bore no name. A card attached to the roses read simply, "Sock it to 'em." Michelle rummaged in her purse, found a pen, and added "Love, John and Michelle" to the greeting.

As Cass left the rehearsal stage, her secretary, Carol Samuels, handed her a cup of hot tea with lemon.

"John and Michelle just checked in," Carol said. Cass took the tea. "Screw 'em," she replied.

The show that evening went badly from the start. As the orchestra was playing her overture, Cass mistook the music for a cue and started singing California Earthquake over a backstage microphone. The mike was quickly shut off, and the overture continued.

"Naomi!" a ragged voice screamed over the music. Heads turned to the center aisle, where Steve Brandt, a gossip columnist for Photoplay, was making an entrance two beats ahead of the evening's star. Brandt, a sort of bush - league Savonarola, makes his living skewering celebrities with their own peccadilloes. He got his start in the gossip dodge by sneaking onto the set of the original American Bandstand in Philadelphia and taking candid shots of the Regulars for teen magazines. He had been observing John and Michelle Phillips ever since they moved into Jeanette MacDonald's Bel Air mansion three years ago. It was partly on their account, and partly to help Cass remember her roots, that he was in Las Vegas. Peter Sellers calls Steve Brandt "the Prince of Darkness," but Peter Sellers always exaggerates.

Cass opened with the old Mamas and Papas favorite, Dancing in the Streets, which some of the audience seemed to recognize. There was a smattering of applause down front as the oleo curtain swept up to reveal Harvey Brooks' six - piece rock combo.

When the song was done, Cass made passing reference to the Mamas and Papas, indicating that while running around with a kinky rock - and - roll act was fine for kids, she was now in the Big Time, and was pleased that you all could come tonight. She did an album plug, then attempted to turn on the fish - cold audience by singing Rubber Band, in which she lyrically invited the roomful of wall - eyed whiskeyswillers to "roll enough to pave the way/To a brighter day." By the time Cass got to California Earthquake, a broken line of patrons could be noticed moving up the center aisle toward the door. Mama Cass wasn't a hippie; she wasn't sexy; and, having nearly killed herself losing one hundred pounds for her solo debut, she wasn't even very fat. At least fat would have been something, so what was there to see? Cass had never become a legend with this crowd. They weren't prepared to sympathize with her raspy, tortured delivery because they carried no memories of her earnest mezzo - soprano tones the way they sounded when she didn't have tonsillitis.

In fact, they were having none of it. No smart - assed songs about pot. No crap about earthquakes. No longhaired bastards with electrified guitars. None of it. Las Vegas, they knew, was the town where Streisand played second banana to Liberace.

The town that regularly scares the pants off Sinatra so bad he works his butt off rehearsing his act. The biggest names in the business crawl into Vegas on their bellies, and this lady can't even sing!

The advance guard of the exodus was back at the slot machines by the time the back lighting revealed the twenty - piece house orchestra in tasteful black - tie outfits. They had been back there behind the scrim all along. The appearance of the orchestra held up the traffic flow in the center aisle momentarily, but a double - edged joke from Cass about the Soviet secret police set whole families to jiggling their silverware as they hurried out of their booths and to the exit.

Down front, at long tables perpendicular to the stage, were two hundred friends, press people, and hangers - on whose tabs were being picked up by the lady in the psychedelic chiffon who was at that moment struggling on stage to make her vocal chords respond to music. The group included a contingent of about twenty from the deeper recesses of the Hollywood Hills who were said to be personal emissaries of Papa Denny Doherty, whose whereabouts were unknown. It was said that Denny rarely left his mountaintop, except to bailout friends, and had decided to make no exception for Cass's opening.

Denny's friends weren't happy when Cass brought out the Castro brothers - all sequins and brilliantine - to sing licorice - sweet counterpoint to Words of Love, which had been translated into Spanish for the occasion. "They've always wanted to work the Big Room," Cass announced proudly, as the quartet broke into an energetic, toothy grin that shot hot Latin love and laughter to the far corners of the auditorium. Quick, poignant glances were exchanged, then shaded, at the front tables. The show was coming apart at the seams and Cass knew it. She battled on, trying to coax mellow sounds from her aching larynx, but they wouldn't be coaxed. High notes were out of the question, and low ones turned into a scratchy hiss. The Los Angeles Times would excuse her illness, but not her lack of preparation.

Reviewer Pete Johnson counted every fluffed line and forgotten lyric. He called the performance "painful," and reminded his readers that once, under different circumstances, Mama Cass Elliot had been "glittering, stunning, and magnificent." In the middle of Sweet Believer, Cass's normally lithe voice was reduced to a crusty whisper as she sang:

On your knees but unconquered

Taxed beyond your strength

Now you know the Prince of Darkness Will go to any length

To keep you from flying, Flying too high."

At the end, the applause was perfunctory, not even polite. On her curtain call, Cass came too far out onto the stage, and the applause stopped dead before she could get off again. The room was now silent, except for the shuffle of patrons who had stayed for the finale.

John and Michelle Phillips sat in a crescent - shaped booth, watching the room empty. During the show, Michelle had mouthed lyrics as Cass sang, and winced when she fluffed her lines. "When we were all together," she said, "one of us could always jab Cass in the ribs so she'd make her high notes." Mama and Papa looked at each other blankly. "Should we go backstage?" Michelle asked, then answered her own question. "Yes," she said. "We have to." John shrugged and followed his wife across the Forum toward the stage. Bobby Roberts and Hal Landers - Cass's managers, who had worked for the Mamas and Papas in the old days last year - were huddled in the side aisle. Roberts managed a smile as Michelle and John approached.

"John," Bobby said. "Did you…like the show?" John stared at Bobby, then broke into a grin. "Gee, Bobby," he said.

Michelle kept walking. "I know. I know," Bobby said. "Do you think she can last a week?" Hal Landers regarded John closely.

"I'd pull her out tonight," John said.

"What's Vegas?" Landers demanded. "Who gives a damn what happens in Las Vegas? It's not like this was some big - time room." John smiled and patted Landers on the arm. "That's right, Hal," he said.

Bobby winced. "Hal had an idea," he said. "It'd never work, of course.

But he thought maybe if you and Michelle and Denny went on with her. I mean the Mamas and Papas. . .." .

"It'd never work," John said.